Influenza is a seasonal virus and each winter, during the flu season, approximately 10% of the people in the USA will become infected and approximately 30,000 people will succumb to infection or associated complications. Our best public health response to these yearly epidemics is vaccination. However, influenza evolves rapidly and the strain used in the vaccine must be constantly updated to maintain vaccine efficacy.

One particular lineage of virus, influenza H3N2 evolves significantly faster than other lineages, and partly because of this, is usually responsible for the majority of seasonal morbidity and mortality. Thus, we need to constantly monitor H3N2 evolution and try to predict ahead of time which strains will take off when choosing a vaccine strain. The World Health Organization (WHO) just met last week and chose to use the strain Switzerland/9715293/2013 as the H3N2 component (along with H1N1 and B components) in the coming 2015-2016 Northern Hemisphere flu season. A strain needs to be chosen in February to allow enough time for vaccine manufacture, and thus vaccine strain selection amounts to predicting evolution of the virus ~10 months in advance.

Richard Neher and I have been developing nextflu.org to analyze currently circulating strains of influenza A/H3N2. I thought I’d discuss a bit here our recent observations and how they mesh with vaccine strain selection for the coming season.

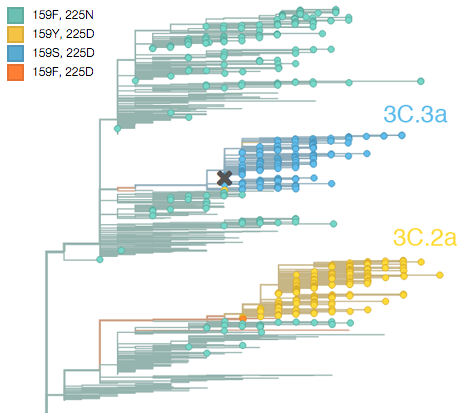

First off, we had a very bad H3N2 flu season this last winter, which was the result of an unusual situation in which the hemagglutinin (HA) gene of two different virus strains or clades each independently mutated to a novel antigenic form. This new antigenic form allowed the mutant viruses to reinfect people who had been previously infected by an earlier strain, resulting in the rapid spread of these mutant strains. The ancestral state was phenylalanine (F) at HA site 159 and asparagine (N) at HA site 225. Both these lineages first mutated at site 225 from asparagine (N) to aspartic acid (D), and then rapidly mutated at site 159 from phenylalanine (F) to serine (S) in one lineage and from phenylalanine (F) to tyrosine (Y) in the other lineage. These replacements can be readily seen in the evolutionary tree of recent viruses:

Above, circles are viruses isolated with the last year and branches are determined by HA sequence. The lineage created by 225D/159S is referred to by the WHO as clade 3C.3a (above in blue) and the lineage created by 225D/159Y is referred to by the WHO as clade 3C.2a (above in yellow). The Switzerland/2013 vaccine strain belongs to clade 3C.3a and is marked with a cross in the above figure. Corresponding to their convergent genetic mutations, these clades appear to be antigenically similar, meaning infection by one will likely provide protection to the other. The WHO report states “Most viruses were well inhibited by ferret antisera raised against cell-propagated A/Switzerland/9715293/2013 (3C.3a) virus and representative 3C.2a viruses, indicating that 3C.2a and 3C.3a viruses were antigenically related”.

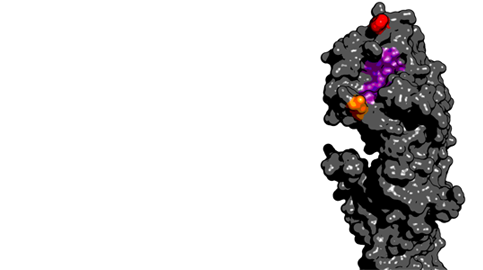

These two mutations both occurred proximal to the receptor binding site on the HA protein:

Thanks to Gytis Dudas for help with drawing the 3D structure.

Here, the receptor binding site is shown in purple, site 159 in red and site 225 in orange. Mutations at site 159 have been been previously demonstrated to have important antigenic consequences. Owing to the observed parallel evolutionary trajectories, it seems likely that in this case, mutation a site 225 potentiated subsequent mutation at site 159.

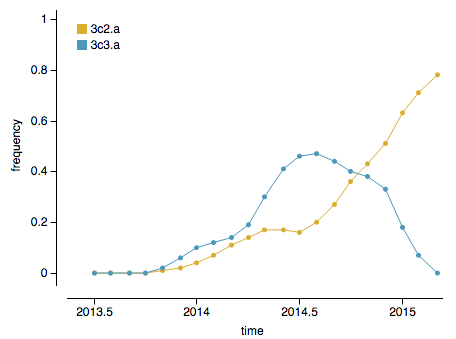

Both 3C.3a and 3C.2a have rapidly expanded and thus, the question at the moment is whether 3C.3a or 3C.2a will dominate in the coming winter season. However, there are indicators that 3C.2a is likely to be the more successful lineage. Viruses with mutations at epitope sites (sites on the protein that are exposed and hence likely subject to antibody binding) generally outcompete viruses with mutations at non-epitope sites. Clade 3C.2a viruses have ~2 more epitope mutations and ~1 fewer non-epitope mutation than 3C.3a viruses, suggesting that 3C.2a is the fitter lineage. Additionally, and more directly, 3C.2a has in the last ~4 months overtaken 3C.3a to become the globally dominate strain:

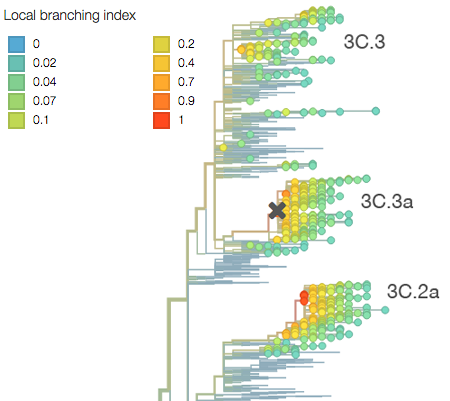

The rapid growth of both of these clades is immediately visible in the phylogeny as clustering of viruses close together on the tree and rapid clade expansion. Here it’s obvious that ancestral 3C.3 viruses are growing slower than 3C.3a and 3C.3b viruses:

This difference in branching rate is quantified by the local branching index, which Richard Neher and colleagues showed to be predictive of future clade success. Clade 3C.2a shows a higher local branching index.

Taken together, these results suggest that clade 3C.2a is the fitter viral clade and thus we expect most infections in the 2015-2016 flu season to derive from 3C.2a viruses. However, this is a rather broad statement and we’re working now to quantify our predictions of clade frequencies in the future virus population.

Critically, the WHO chose to use a 3C.3a virus in the 2015-2016 vaccine. However, from serological analysis they believe that 3C.3a and 3C.2a viruses have a high degree of cross-immunity. In this case, we expect vaccination with a 3C.3a virus to elicit strong immunity against 3C.2a infection. Still, as more data comes in we can expect to see antigenic relatedness between clades to be more fully defined.