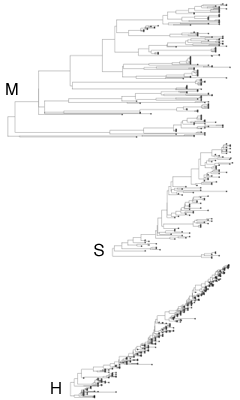

In my paper on selection in viral phylogenies, I compared the effective population size of measles virus to the effective population of human influenza virus. The concept of effective population size Ne is central to population genetics. It measures the timescale of population turnover, or, looking backwards in time, it measures how long it takes for individuals in the population to find a common ancestor. Genetic diversity is a combination of this timescale and mutation rate.

This is just a small addendum to that paper. I had wanted to include swine influenza in with the comparison of measles virus and human influenza virus, but decided that this would detract from the paper’s focus. Here, the sequences of swine influenza come from de Jong et al. (2007).

The scaled effective population size Neτ of measles is estimated at 124.6 years, Neτ of global H3N2 human influenza is estimated at 7.2 years, and Neτ of European H3N2 swine influenza is estimated at 24.1 years.

This fits nicely with the observed patterns of antigenic evolution. Infection with measles confers life-long immunity; evolution of the measles genome does not change its antigenic phenotype. This results in neutral population dynamics. However, human influenza evolves in antigenic phenotype very rapidly, causing strong selective pressures that reduce effective population size. Swine influenza presents a nice example between these two extremes. In comparing rates of antigenic evolution, de Jong et al. find that “while human H3N2 viruses have evolved at a rate of about 2.0 antigenic units per year since 1982, swine H3N2 viruses have evolved more than six times more slowly, about 0.3 antigenic units per year.” In this case, selective pressures still reduce effective population size, but not to the degree seen in human influenza.