We’ve just posted a manuscript to bioRxiv on transmission dynamics of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus or MERS-CoV. MERS-CoV has been identified as the cause of sporadic outbreaks of severe respiratory illness in the Middle East, largely in the Arabian peninsula, since 2012. Its epidemiology has sometimes been described as mysterious, since only the most severe cases are usually admitted to hospitals, sometimes without reports of contact with camels, the accepted reservoir for the virus. That, as well as large hospital-associated outbreaks of MERS, have suggested that there should be a sizeable community transmission contribution to the ongoing outbreaks.

Although parallels between severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and MERS-CoV were inevitably going to be drawn, there have been clear indications that MERS-CoV is a different kind of beast. Unlike SARS-CoV that spread rapidly to other countries, primary MERS cases have been restricted to the Arabian peninsula and outbreaks outside of it have been brought under control relatively quickly. This is a pattern strongly suggestive of a repeated zoonotic spillover where the virus is jumping into humans repeatedly in the area where the reservoir and humans overlap, but the virus transmits poorly between humans and goes extinct. Despite these kinds of evidence this pattern has not been clearly confirmed. We thought that genomic sequences could provide an ideal window into these epidemiological patterns.

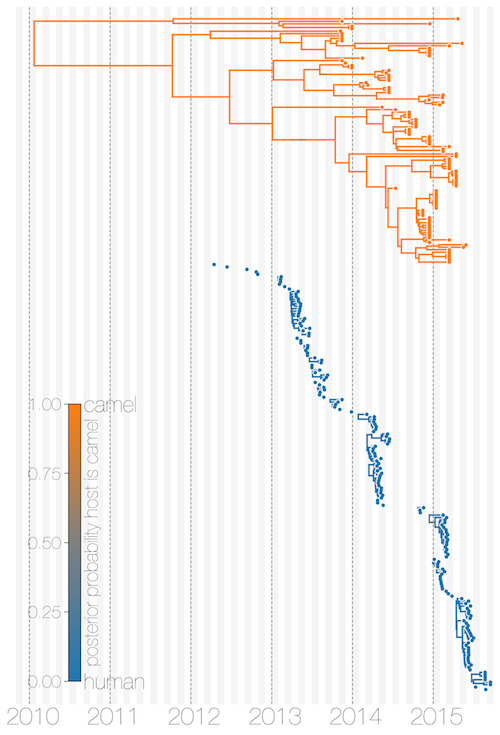

In order to establish cross-species transmission with sequence data one would ideally need a large sample of viral sequences from the reservoir as well as the ‘sink’ host. These data exist for MERS-CoV, but have been sampled very unevenly. MERS-CoV genomes that we have collated are heavily skewed towards the human side (174 genomes) compared to the camel reservoir (100 genomes), in addition to human sequences coming predominantly from hospital outbreaks. What has been clear so far is that MERS-CoV sequences from camels are more distantly related to each other on average than MERS-CoV sequences from humans, but most ancestral state reconstruction methods that could be used to infer the host of MERS-CoV lineages are agnostic to such signals. This is where the structured coalescent comes in. By explicitly modelling the evolution of MERS-CoV in a population structured along host boundaries we can estimate migration rates between the two hosts.

We find exactly what we would expect – MERS-CoV is almost exclusively a virus of camels and humans are an incidental and ultimately dead-end host. None of the 56 viral lineages we saw entering humans ever made it out of humans to contribute to the long-term evolution of MERS-CoV. We went a bit further here and applied the logic we used in our paper on Zika virus in Florida. Having identified the cross-species transmission events we could ask what the distribution of clade sizes resulting from those spill-over events tells us about MERS-CoV transmissibility. We estimate that the basic reproductive number for MERS-CoV is almost certainly below 0.91, indicating that it is unlikely to establish self-sustaining transmission chains in humans. The corollary of this is that there must have been hundreds of MERS-CoV spill-over events from camels into humans, most probably restricted to primary cases.

What does this all mean for public healthcare response? For one, it’s clear that camels are the sole focus of MERS-CoV evolution and until it is controlled there humans will be at risk. Second, as mentioned previously, MERS-CoV is different from SARS-CoV and the evidence so far indicates that MERS-CoV does not do so well in humans. And even though there is no selective pressure on the virus in camels to transmit effectively between humans, repeated spill-over events mean that if such a variant were to emerge in camels it is very likely to find itself in humans eventually. Lastly, there is (again) much to be said about sequence data. We are not at a stage where we can identify pathogens before they spread widely if they are good at human-to-human transmission, but for viruses like MERS-CoV that are new and capable of generating stuttering transmission chains sequence data are ideal. Genome sequences, when gathered consistently, across affected areas with appropriate metadata are an incredibly powerful tool that combines diagnostics, typing and detailed evolutionary history in a single standardised bundle that can be used and shared easily.