How many strains of flu are circulating at any given moment? And how much sampling is necessary to capture this diversity? This came up in a conversation with Andrew Rambaut and Erik Volz last week. Fortunately, we can get a back-of-the-envelope estimate using standard population genetic theory. Here, I’ve downloaded all the amino acid sequences for the HA1 region of the H3N2 hemagglutinin protein that exist in Genbank between January 2002 and June 2009. This figure is looking at 10 week windows, with each colored region representing the frequency of a particular sequence in that window’s sample. You can see that there are a few common sequences and many rare sequences, and that sequence diversity rapidly changes over time. The HA1 region is the region of the influenza genome most responsible for antigenic variation. Evolution of HA1 is what allows the virus to infect people that have built up immunity to previous strains of flu. Looking at amino acid diversity of HA1 will give an under-estimate of total genomic diversity of flu, but should be a decent proxy for functional diversity.

We can use the Ewen’s sampling formula to calculate the probability that we observe k distinct sequences (or alleles) in a sample of n sequences. In this case, the expected number of alleles in sample of n sequences is

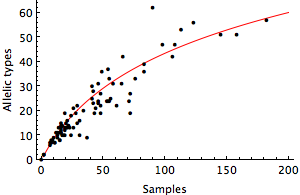

where θ represents the level of mutational input into the population. This formula assumes neutral demography, no geographic subdivision and an infinite alleles mutation model, where every mutation creates a new allele. I fit this formula to the windows from Genbank comparing the number of sequences sampled each month to the number of distinct sequences observed. Doing so, I get an estimate for θ of 28.8, shown in red.

With this number in hand, it’s possible to estimate the number of distinct alleles that one would find in a very large sample. We expect to find 104 alleles in a sample of 1000 sequences and 169 alleles in a sample of 10k sequences. Estimated global prevalence of influenza is around 70 million (more during the northern hemisphere winter, but this should be good enough for our purposes). A sample of 70 million sequences is expected to have 358 distinct sequences. However, most of these are at very low frequency. We would only expect to see around 30 alleles at greater than 1% frequency, 86 alleles present at >0.1% frequency and 164 alleles present at >0.01% frequency in the population. I’m not sure exactly where to draw the line in terms of “important” variation, but I would think that 1 in 1000 is a good ballpark. Thus, it seems to me that a sample of around 500 sequences (with an expected 84 unique alleles) would be sufficient to capture all the possibly important diversity in the HA1 protein.