Our newest study is now available as a preprint on bioRxiv! This work was done by Sidney Bell, Leah Katzelnick, and Trevor Bedford. You can find all the data, code, figures, etc etc. in the repository here.

The tl;dr

- Dengue virus is a mosquito-borne, emerging pathogen common in tropical regions

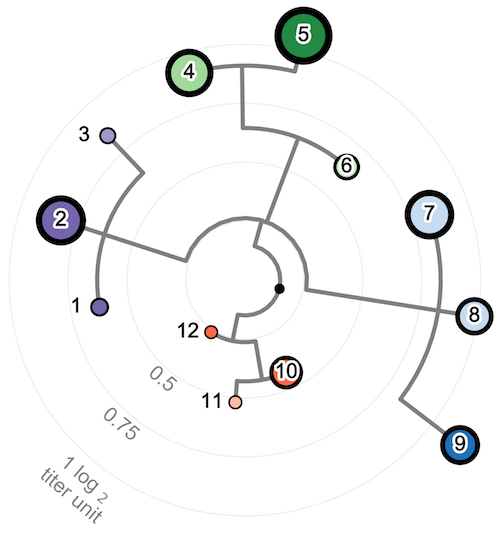

- While we used to think there were only 4 kinds of dengue that your immune system recognizes as distinct from one another, we identify at least 12 antigenically distinct kinds of dengue.

- We also found that in Southeast Asia, population immunity and antigenic differences between dengue virus strains has a big impact on which kinds of dengue will circulate in a given season.

Background: dengue virus is an emerging pathogen, and kind of a weird virus

Dengue virus circulates widely in tropical regions of the world, and about half of the global human population is at risk of infection each year. While most infections are mild, a small subset of cases develop into very severe dengue fever, causing 10-15,000 deaths each year. Most countries in Southeast Asia and South America experience annual dengue epidemics, but it’s difficult to predict year-to-year which countries will have a mild or severe dengue season. This is problematic because our best bet for preventing dengue-related fatalities is preemptively controlling the mosquito population (we don’t yet have a good dengue vaccine).

One of the reasons why we can’t yet vaccinate against dengue or foresee severe epidemics is because from a virologist’s perspective, dengue virus is a little weird. For most viruses, you get sicker the first time you’re infected (“primary infection”) than the second (“secondary infection”). That’s because during your primary infection, your body generates an immune response and then remembers how to fight the virus the second time around. Most dengue cases follow this pattern, where the immune response learned during your primary infection helps protect your body against a secondary infection. For some dengue cases, however, this immune memory can backfire, and can actually help the virus cause severe disease. Usually, this happens when the specific strains of dengue virus that caused your primary and secondary infections look pretty different from each other to your immune system (we’d say they have distinct “antigenic phenotypes”).

Question 1: how many different kinds of dengue are there (as far as your immune system is concerned)?

So, we know that differences between antigenic phenotypes are important for determining whether your immune response is protective or harmful during your secondary infection. The tricky part, though, is that we don’t know exactly which viral characteristics change its antigenic phenotype (how it looks to your immune system), or even how many distinct antigenic phenotypes there are. If we can figure this out, it could potentially help researchers design better vaccine candidates (by choosing strains to include in a vaccine that will generate a wholly protective immune response).

We have a few clues to start with. Genetically, dengue viruses are super diverse: there are four major types of dengue virus (called “serotypes”), and we know that these serotypes are antigenically distinct from one another. It’s historically been assumed that all the virus strains within a given serotype are antigenically identical to one another, even though they may be pretty genetically diverse (spoiler: turns out this isn’t the whole story). Three years ago, Leah Katzelnick and her coauthors did some beautiful work to experimentally measure how antigenically different a bunch of dengue strains are from one another (i.e., how well does the immune response generated against your primary infection with strain A protect you against secondary infection with strain B). Their initial study suggested that some dengue strains from the same serotype may be antigenically different from each other. In our new study, we reanalyzed this dataset (hooray for open science!) to try and understand how extensive these differences were, what caused them, and how much they mattered.

Answer 1: at least 12!

Using a phylogeny-based model, we mapped how genetic relationships between viruses correspond to the antigenic differences between them. We found that as viruses diverge genetically, they also tend to diverge antigenically. We identified at least 12 distinct antigenic phenotypes of dengue virus, suggesting that the antigenic relationships between dengue strains are more nuanced than previously believed. This also suggests that there is much more to learn about how dengue evolves and interacts with the immune system. We hope this will help other researchers’ important efforts design a broadly protective dengue vaccine.

Question 2: Ok, so how much do these antigenic differences matter in the real world?

We also wanted to know whether this could help us predict which dengue virus strains would be circulating in a given season. Logically, as a virus circulates in a population, the proportion of the population that is susceptible to infection with that virus — and other antigenically similar viruses — decreases over time as more people acquire immunity. Thus, virus strains that are antigenically distinct from recently circulating strains are better able to escape this population immunity, allowing them to infect more people and circulate more broadly.

Answer 2: Population immunity has a big impact on which kinds of dengue will circulate in a given season.

We leveraged our new understanding of dengue antigenic phenotypes to estimate the proportion of the population in Southeast Asia that was immune to each kind of dengue virus over time. We found that this enabled us to predict which dengue strains would predominate in a given season with reasonable accuracy. This demonstrates that fluctuations in the dengue virus population are strongly driven by antigenic differences between viral strains. We hope that this can eventually help us predict which countries will experience a mild versus severe dengue epidemic in a given season, which would help public health officials allocate resources most effectively. However, it’s important to keep in mind that predictions of viral population dynamics are kind of like your local weatherman’s predictions: while we can use our understanding of underlying processes to make sound predictions, there’s always some level of uncertainty (in our case, our predictions of whether a serotype will increase or decrease over the next 5 years are accurate about 80% of the time).

Thank you!

We would like to thank Richard Neher, Molly OhAinle, David Shaw, Paul Edlefsen, Michal Juraska, and all members of the Bedford Lab for useful discussion and advice.

We also thank the scientists who helped generate and analyze the original antigenic dataset — our research wouldn’t be possible without your commitment to open science: Judith Fonville, Gregory D Gromowski, Jose Bustos Arriaga, Angela Green, Sarah James, Louis Lau, Magelda Montoya, Chunling Wang, Laura VanBlargan, Colin Russell, Hlaing Myat Thu, Theodore Pierson, Philippe Buchy, John Aaskov, Jorge Muñoz-Jordán, Nikos Vasilakis, Robert Gibbons, Robert Tesh, Albert Osterhaus, Ron Fouchier, Anna Durbin, Cameron Simmons, Edward Holmes, Eva Harris, Stephen Whitehead, Derek Smith.

Finally, a huge shout out to the open-source developers who build and maintain the packages we heavily rely on to get science done: numpy, pandas, scipy, biopython, scikitlearn, matplotlib, seaborn, and many others.