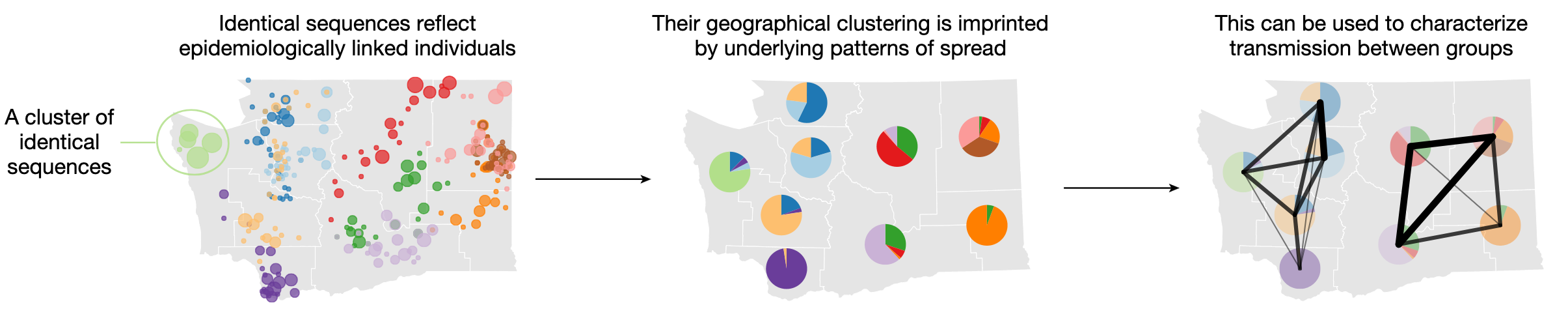

Our work on analyzing patterns of occurrence of pairs of identical sequences between population groups was just published in Nature! There, we present a new method developed to characterize transmission at the population level by analyzing the groups (e.g. age groups, geographies) in which pairs of identical sequences are collected. The rationale for our approach is explained in Figure 1. As mutations accumulate in pathogen genomes over successive transmission generations, epidemiologically linked individuals are infected by genetically similar pathogens. Among these genetically close pathogens, identical sequences capture the most epidemiologically linked individuals. Intuitively, if transmission is frequent between regions A and B, we expect to observe many pairs of identical sequences between these two regions.

Figure 1. The clustering of identical pathogen sequences across population groups reflects underlying disease transmission patterns at the population level and can be used to characterize patterns of spread between groups. In this toy figure, each color represents a different cluster of identical sequences.

We designed a relative risk (RR) metric that quantifies how many pairs of identical sequences are observed between two population groups compared to expectations from where pairs of identical sequences are coming from. To apply our RR framework, we used a large SARS-CoV-2 sequence dataset coming from WA genomic sentinel surveillance (more than 114,000 sequences with matched metadata that include age and home location information). We found that occurrence patterns of identical sequences between counties are consistent with local spread (with identical sequences being particularly enriched in pairs observed within the same county or between geographically close counties), while also being imprinted by the geographical structure at the state level. When comparing the RR of observing identical sequences between counties with the RR of movement between counties (estimated from mobile phone and commuting mobility data), we find a strong agreement between these two data sources. We also investigated outliers in the relationship between sequence and mobility data, which we were able to link with transmission between postal codes with male state prisons.

We additionally looked at occurrence patterns of identical sequences between age groups, which we found to be highly consistent with expectations from social contact data. We found that transmission patterns between age groups differed across spatial scales, for example with identical sequences having an increased risk of being observed within the same age groups at shorter geographic distance, suggesting that these type of transmission events rather occur at the local level.

The last decade has propelled us to a new era in terms of pathogen sequence dataset size, but existing phylogeographic approaches tend to be computationally very costly and hence unable to fully leverage these large datasets. We hope our approach is a helpful contribution to the study of these very large datasets by circumventing the need to infer a phylogenetic tree and directly relying on identical sequences. In former work, we had already leveraged these identical sequence clusters to infer the reproduction number and transmission heterogeneity from their size distribution. These two pieces of work highlight the potential for methods studying genetically proximal sequences in uncovering both key transmissibility parameters and transmission patterns between population groups.