We just posted a paper to bioRxiv looking at the dynamics of cross-species transmission of SIVs (HIV’s close relatives that infect other species of primates). This was my Epidemiology MS thesis project here in the Bedford lab, and was my first computational project.

SIVs infect over 45 different species of primates, and HIV emerged as a human pathogen through at least 12 independent transmissions of SIVs from chimpanzees, gorillas, and sooty mangabeys to humans. Individual occurences of SIVs switching hosts have been sporadically documented, but we still had no idea how regularly SIVs switch hosts – i.e., we had no idea whether or not the transmissions that sparked the HIV pandemic were unusual occurences.

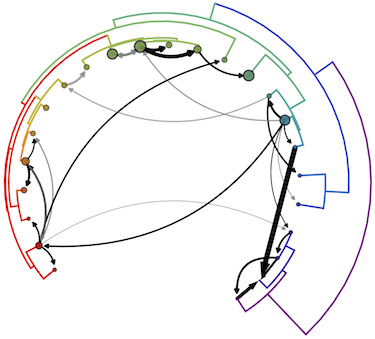

Many of these viruses have been sequenced in recent years. While we weren’t able to study them all, we were able to get enough sequence data (shout out to the fantastic Los Alamos National Labs database) to study the history of SIV cross-species transmission (CST) among 24 different primates. We used this data to assess how frequently viruses from different lineages recombine (part of one genome and part of another genome getting “pasted together”), and to look at how often they’ve switched hosts over evolutionary time. Our phylogenetic analysis found that SIV evolution has been shaped by at least 13 instances of interlineage recombination, and identified 14 novel, ancient CST events. We found that on average, each linaege of SIV switches hosts about once every 6.25 substitutions per site (these are funny units because SIVs are millions of years old, but they essentially mean the amount of evolutionary time required to see 6.25 substitutions in each site of the genome). We also observed more CST events between closely related primates, and find that viruses and hosts have extensively coevolved (and likely cospeciated). Taken together, our results show that SIV biology has been extensively shaped by CST, but it’s still a rare phenomenon over evolutionary time.